By Joseph Berger

Published Nov. 23, 2022

In the summer of 2001, Harriet Bograd decided to visit her daughter Margie, who had taken a summer job in a remote village in Ghana.

When Ms. Bograd and her husband, Ken Klein, arrived in the village, Sefwi Wiawso, they learned about its community of two dozen families who considered themselves Jewish, even if the religious authorities in Israel and elsewhere did not.

In the week she was there, Ms. Bograd, whose husband called her “one of life’s great enthusiasts,” turned her enchantment with the villagers into a practical project that has become a major source of income for the community. She guided artisans in fashioning the colorful kente cloth sold in the local market into covers for the braided challahs that observant Jews bless and eat during Sabbath and holiday meals. A trained lawyer, she set the community up as an incorporated business that sold the challah covers across the United States for $36 apiece. Thousands have been purchased.

In the years after that trip, Ms. Bograd worked with the nonprofit organization Kulanu, which supports “isolated, emerging or returning” Jewish communities in places where even most American Jews don’t realize there are Jews: Uganda, Tanzania, Nigeria, Cameroon, Madagascar, Indonesia, Pakistan, Guatemala, the Philippines and more — 33 countries in total.

These are people who for generations have kept some fundamental Jewish laws, like resting on the Sabbath and abstaining from certain foods, but who may have had only opaque ideas of their community’s Jewish origins.

They trace their Jewish roots to a variety of sources: the 10 lost tribes that were dispersed by the Assyrian conquest of the Kingdom of Israel in 722 B.C.E.; the Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions, which, starting in the late 15th century, scattered thousands of Jews in far-off lands, where many practiced their religion in secret; and the century-old conversions by communal leaders more attracted to the Old Testament than the teachings of Christian missionaries.

“It gave her such joy that these Jewish people felt they were connected to the greater Jewish world and felt they belonged,” Mollie Levine, the deputy director of Kulanu, said in an interview.

Ms. Bograd died on Sept. 17 in a Manhattan hospital. She was 79. Her daughter Rabbi Margie Klein Ronkin said the cause was complications of heart surgery.

So exhilarated was Ms. Bograd by her experience in Ghana that she promptly joined the board of Kulanu. By her death, she had served as its president for 14 years. The organization’s headquarters were in the study of her Upper West Side apartment.

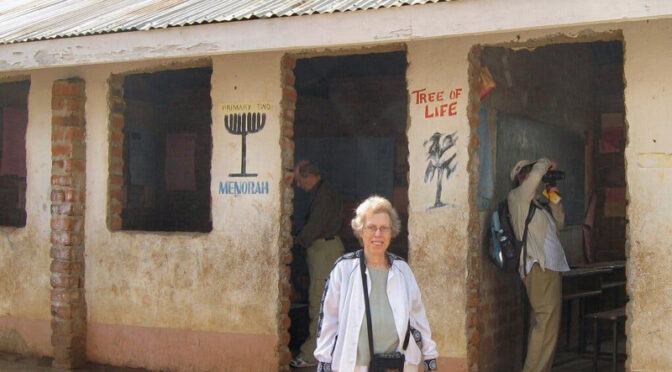

Under her command, the organization, whose Hebrew name means “all of us,” raised funds to build synagogues in Uganda and Zimbabwe; a Jewish-themed primary school in Uganda that is open to Christians and Muslims; and a mikvah — a ritual bath — in Tanzania. With a budget of around $500,000, Kulanu has also provided rabbinical training and advanced classes in Judaism at American seminaries for community leaders and distributed prayer books, Torah scrolls, prayer shawls and other ritual items.

Kulanu’s work has not been without controversy. While Jews in Ethiopia have been recognized by the Orthodox authorities in Israel as authentically Jewish, those in other parts of Africa have not been. Efforts by Conservative rabbis to formally convert some Africans to Judaism have encountered challenges because the Orthodox establishment in Israel does not recognize the legitimacy of Conservative rabbis. Bonita Nathan Sussman, Kulanu’s new president, said that many Africans also reject conversion, arguing, “Who are you to tell me I’m not Jewish?”

On the other hand, Ms. Levine said, Ms. Bograd “met them at the level where they are.”

She was active in Jewish causes in New York as well. In the early 1980s, she and other parents partnered with educators to found the Heschel School, a Jewish day school in Manhattan that now enrolls about a thousand students. And at the West End Synagogue, a Reconstructionist congregation, she was known for the warm way she greeted newcomers, an act congregants affectionately called “Bograding.”

Harriet Mary Bograd was born on April 6, 1943, into a Conservative Jewish home in Paterson, N.J. Her father, Samuel Bograd, owned an upscale furniture emporium with an uncle. Her mother, Pauline (Klemes) Bograd, sometimes helped her husband with his business and was a leader in a local chapter of Planned Parenthood.

Harriet attended a special high school operated by Montclair State Teachers College (now Montclair State University) and graduated from Bryn Mawr in 1963 with a degree in political science. The summer she graduated, she arranged for a group of nine white Bryn Mawr students to teach at Livingstone College, a historically Black college in Salisbury, N.C., so that they could absorb the impact of the growing civil rights movement.

One of 11 women in her class at Yale Law School, she graduated in 1966. Rather then joining a law firm, she went to work for an organization in New Haven, Conn., that represented indigent clients in matters like access to medical care and that trained local residents to be advocates for themselves and their neighbors.

She helped start a day care center in New Haven, joined with other parents and teachers in a drive to improve local public schools, and campaigned for the government to approach drug addiction as a crisis of health and poverty rather than a crime.

She married Mr. Klein, a tax lawyer, in 1977. In addition to her daughter Rabbi Klein Ronkin, he survives her, as do another daughter, Sarah Klein; a sister, Naomi Robbins; and two grandchildren.

When Ms. Bograd received a diagnosis of Stage 4 breast cancer in 1997 with a bleak prognosis, it made her only more determined to use her remaining time for the Hebrew concept of tikkun olam — “repairing the world” — and for her work with Kulanu.

Jonathan Sarna, a professor of American Jewish history at Brandeis University, said Ms. Bograd had also seen Kulanu as a vehicle to expand the mainstream Jewish sense of what Jews are supposed to look like.

“She felt it enhanced American Judaism to recognize that all Jews are not white and European,” he said.

Joseph Berger was a reporter and editor at The New York Times for 30 years. He is the author of a biography of Elie Wiesel, which is scheduled for publication in February.