By Viviane Spiegelman

My journey into a world of whispers and shadows started 30 years ago in San Antonio. I had just visited the iconic Alamo where the Texan forces were slaughtered by the armies of Mexico’s Santa Ana. I felt their ghosts.

To say the least, it was an intense experience, so my friend and I took a head-clearing walk along the Paseo del Rio. We came across a tiny structure that was billed as The Spanish Governor’s Mansion. Curious, we went inside, where almost immediately, an ornately carved Baroque secretary desk caught my eye. I went over to it to examine it in more detail.

When I pushed back the panel covering a collection of tiny drawers, my heart skipped a beat. There, in the centre of the bank of drawers was a mogen dovid!

What on earth was it doing there in this city of seven Spanish missions and polychromed virgins?

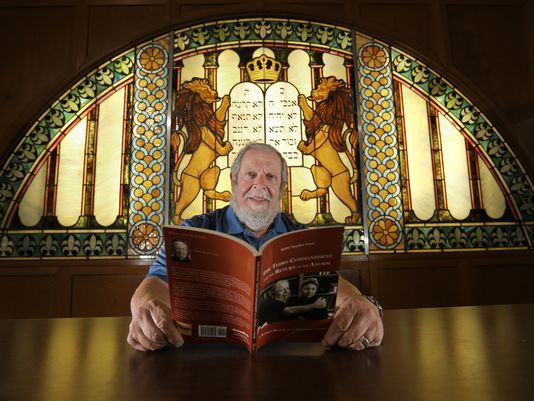

But life happened, and I had almost forgotten about this curiosity until I read an interview years later with El Paso’s Rabbi Stephen Leon in The Jewish Tribune. Perhaps he knew something about the desk? So I looked up his email (it’s on his synagogue’s website) and wrote him a letter. He suggested that I might want to read To the Ends of the Earth, by Stanley Hordes, New Mexico’s state historian. It was available at the Toronto Public Library.

But life happened, and I had almost forgotten about this curiosity until I read an interview years later with El Paso’s Rabbi Stephen Leon in The Jewish Tribune. Perhaps he knew something about the desk? So I looked up his email (it’s on his synagogue’s website) and wrote him a letter. He suggested that I might want to read To the Ends of the Earth, by Stanley Hordes, New Mexico’s state historian. It was available at the Toronto Public Library.

Hordes details the research done on New Mexico patients who were afflicted with a particular skin disease. The research revealed that a higher than expected number of them carried Sephardic Jewish genes. He details the journeys of frightened conversos through El Paso to the relative safety of the most northern reaches of the Spanish empire, an area we now call New Mexico. They were seeking refuge from the tribunals of the Spanish inquisition that had extended its tentacles to New Spain.

The book was an eye-opener. It told me nothing about the desk I had seen in San Antonio, but it left me with two questions: When and why did Jews become Christian?

So I went off to the Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto, where I was invited to audit any courses I might find of interest. I have a BA in history, so I gravitated to the history courses. My first course examined what is referred to as the Early Modern period,1450 to about 1720. It included a study of the Spanish Inquisition, which was authorized by the Pope in 1478 but did not go into effect for several years.

Contrary to popular opinion, the Inquisition did not go after Jews. Its target was heretics, and the converts were likely suspects even though by the time the Inquisition set up shop there were very few unbaptized Jews left in Spain. The widespread massacres of 1391 and the unrelenting social and economic pressures throughout the 1400s had been effective. So many conversos were third or fourth generation and most barely knew what Judaism was.

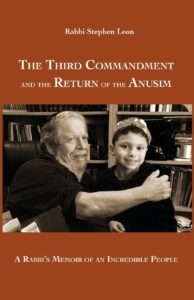

A quote from a review of Rabbi Leon’s new book, The Third Commandment and the Return of the Anusim: A Rabbi’s Memoir of an Incredible People — which was published in July — summarizes the situation of Spanish Jews at the end of the 15th century:

“These forced conversions changed the social structure of Spanish Jewry. Where once there had been a single and united Jewish politic within the various nations that composed the Iberian Peninsula, now Jewry was divided into four separate subcategories:

(1) Jews who were practicing members of the people of Israel,

(2) Jews had converted to Christianity due to issues of spiritual assault but despite the legal and economic hurdles remained at least in private loyal to their faith and people,

(3) Jews, who were forced to convert, decided to adapt themselves to their new situation and became loyal Catholics and

(4) a small number of Jews who for personal reasons had freely chosen Christianity.”

The Spanish Inquisition looms large in our imagination for several reasons:

- It went on for 344 years

- It was not confined to Spain and Portugal but to the entire Spanish empire

- The auto de fe was designed to shock and awe

- Some of the psychological and physical tortures devised by the Disquisition are still with us today (e.g. water boarding)